Blog

Space is a powerful vantage point for monitoring the interplay between human activity and environmental health. The common thread through monitoring of Earth’s weather, climate, and surface is that data collected from space allows people on Earth to make well-informed decisions regarding sustainability.

Is the current level of commercial space growth sustainable? What does sustainability even mean? As chief scientist at an engineering firm specializing in space and sustainability systems, and as a human who enjoys the serenity of the wilderness, I feel obligated to grapple with these questions.

Medical professionals could learn a thing or two from spacecraft systems engineers. As with spacecraft development, compartmentalizing medical treatment into ever-smaller disciplines without mechanisms of communication between them is a recipe for pain.

We describe the relationship between mission cost and risk, examine the state of low-cost missions in the PSD, list the benefits of further commercial involvement to planetary exploration and its community, and provide a set of incentives that would evolve beyond the CLPS program by attracting further engagement by commercial space companies.

Read a white paper I wrote with a team on a mission concept to Venus called Thalassa.

Watch a virtual panel discussion I participated in about career planning in the space sciences.

I joined Jake Robins on the WeMartians podcast to discuss the changing paradigm of how we explore the solar system.

How do those in leadership roles on NASA missions manage their teams? How did they prepare for the role they’re in? How did they build teams that work together well? How do they foster a healthy team culture? Here’s the panel discussion I organized to get answers to these questions.

My Lunar & Planetary Science Conference 2020 abstract was rejected for related to policy and not science or missions. In my continued effort to bridge the gap between planetary science and commercial space, here’s my rejected abstract.

I wrote a commentary for the October 2019 issue of Physics Today on my experience and lessons learned from leaving academia.

After a few years of working with engineers, I look back on my MESSENGER experience with a fresh perspective and an appreciation for the engineers I never met who created and operated the spacecraft. Now at First Mode, I use this experience to bridge the communication gap between scientists and engineers.

Every time a spaceflight failure occurs, the phrase “space is hard” will invariably be uttered in response. What is it that makes space so hard?

I organized a successful panel about non-academic careers at a planetary science conference. However, I had previously underestimated the level of toxicity regarding nontraditional career paths despite having experienced it firsthand.

The first step in effecting change is admitting that there is a problem. In order to disrupt the status quo, the planetary science community must first make changes in our culture and assumptions regarding missions.

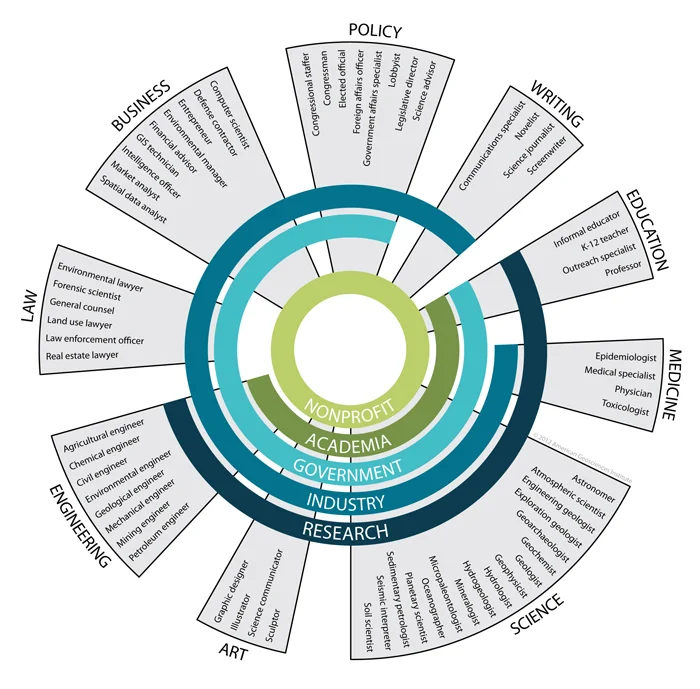

All too often, Ph.D. students leave grad school with no idea of how to find jobs outside a traditional academic or research career track. If you’re in that boat, here are some resources to get started.

Interested in working in commercial space but not sure which companies to target in your job search? Check out this map of the NewSpace ecosystem.

With the advances in small satellite technology and the success of the MarCO CubeSats at Mars, it's time to revisit lessons from NASA's 1990s Faster, Better, Cheaper era.

One of the most critical elements of a successful space mission is effective communication between two species: scientists and engineers.

Here are some resources for figuring out what non-academic career options might be available to you.

I want to break this stigma of leaving academia by describing why I left. I didn’t have anyone to turn to who could validate my feelings, so I hope that I can do that for others.

I left academia because I didn’t feel like it was the right environment for me, despite my love of planetary science. Here I describe my journey going from academia into industry.

Many commercial space companies don’t seem to think they need planetary scientists on staff. They are wrong.

Upon hearing the word “networking,” most people probably envision a room full of strangers, mediocre hors d'oeuvres, and moderate to high levels of anxiety. It’s the worst, right?

If you start applying to industry jobs without first doing these three things, your application will just be flushed down the digital toilet.

Some people think they would be happy in industry until they learn more about it. As you consider whether to pursue a career in industry, consider these 3 questions that I always ask when interviewing academics.

After identifying interesting sectors in industry, it’s time to narrow your focus and discover potential positions and employers. Here’s how.

Developing a roadmap for your new career direction will require serious thinking about your interests and priorities. The first step I took was to isolate myself from distractions and scribble stream-of-consciousness answers to these questions.

Anyone who’s been in a Ph.D. program knows the term “mastering out”: leaving a Ph.D program and getting a masters as a “consolation prize”. While there’s no slang to describe someone who leaves research, in planetary science, the scorn is no less insidious.

Through this blog, I hope to reframe the narrative about planetary scientists leaving academia, provide direction I didn’t have on how to get an industry job, and share insight into the space mission engineering process from a NewSpace perspective.

Now is an exciting time for space exploration. In our excitement, we should recall the mistakes made in the past here on Earth and work intentionally to ensure we are not repeating them. An absence of regulation does not mean there is an absence of ethical obligation to maintain sustainable space environments for future generations and for the intrinsic value of space itself.